How to build team synergy by emulating a pit lane crew

This article is part of our series on how to help students develop their collaborative superpowers and maximise the effectiveness of working in teams across a PBL project. To learn more about how we teach collaboration, see here.

The theory of teams is that they are able to achieve more than any one individual and, as such, working in teams is the best way to solve substantial problems and tackle significant tasks. This relies on the team being able to create synergy, where the team as a whole are greater than the sum of their parts.

We often use the analogy of a Formula 1 pit-lane crew with students when we talk about what it means for a team to have synergy. A team of people all performing a complex array of jobs can complete a pit-stop – which requires the changing of tyres, refuelling, and fixing of damage – in an average of just over three seconds. That is a staggeringly short amount of time and is perhaps the best example of synergy that we can think of. If one person was left to do all the work required in a pit-stop, it might take minutes.

Too often, however, teams don’t create synergy. These teams don’t resemble a finely-oiled machine where the contributions of each team member are assimilated and amplified to create a single, successful output. Instead, these teams look more like a cobbled-together group of misfits who are pulling in different directions, unable to coordinate their respective efforts. In these teams, it often takes longer to do the work than if one student just did it all – team members duplicate work, don’t work on the right thing, or produce sub-standard work that needs to be re-done.

If we take our Formula 1 pit-lane team as the paragon of synergy, we can see that two criteria must be present for a team to create synergy. These same criteria must be replicated by students across a PBL unit if they are to attain the same outcome:

Students must know what success looks like

Students must know exactly what they need to do to help the team succeed

Defining success

Of course, students should define success at a macro level by setting team goals for what they want to achieve across a unit. That’s akin to a Formula 1 team setting a goal of winning the championship at the end of the season. But on a micro level, the Formula 1 team also goes into each race with a specific goal and, on an even more granular level, goes into each pit stop with a clear objective; complete the pit stop in x time and successfully make y changes to the car.

For students, this means that they should be setting goals for every task across a PBL unit. These goals should encompass their desired output for that task and what it should look like. These lesson- or task-specific goals are called success criteria.

Success criteria are the evaluative measures that students use to determine when they have achieved the established learning goal or objective. Success criteria typically break down the task or skill into meaningful, achievable chunks that relate directly to the work that students do.

Success criteria should contain both input goals and output goals. Output goals are the end visible outcomes of the work – what they want to have achieved and produced by the end of the task – but the input goals are just as important. They help students define what work is needed to achieve the desired output goal. They effectively act as a checklist – if all input goals are hit, the output goals should be achieved almost by default.

Not every task requires students to create success criteria. An easy (if slightly imperfect) distinction can be made between tasks where students apply and consolidate existing knowledge, and tasks where students create new knowledge in the context of the project. The former might relate to students completing an experiment in class and then analysing the results; the latter, by contrast, might require student research of a problem or the development of an idea or prototype. In these cases, where the work is more complex and multi-faceted, having success criteria is important for students in both understanding what success looks like at the end of the task and the markers of progress along the way which they can monitor to ensure they are on track.

It is recommended that students develop success criteria for key tasks, or that teachers develop success criteria with the class before students commence it. This provides teachers the opportunity to identify the level of student understanding of a concept or skill by listening to what students identify as being important to include in success criteria. Additional guidance or explanation can then be provided if knowledge gaps are apparent.

Individual roles

Once teams have defined what success looks like for each task, and what needs to be done to achieve that success, teams should break success down to an individual level. What does each team member need to do to ensure the team hits its stated objectives?

Individual roles can be either strategic or functional. We recommend that students occupy both strategic and functional roles for each task.

Functional roles are easy to define as they come directly from the input goals defined by the team in their success criteria. These input goals can be broken up between the four team members so that, across the team, everyone knows exactly what to work on, when it is due by, and to what standard that work must be done.

Strategic roles, however, are broader and sit above the input tasks a student must complete for the task to be completed. They speak to the broader role the student must play within the team to ensure team cohesion.

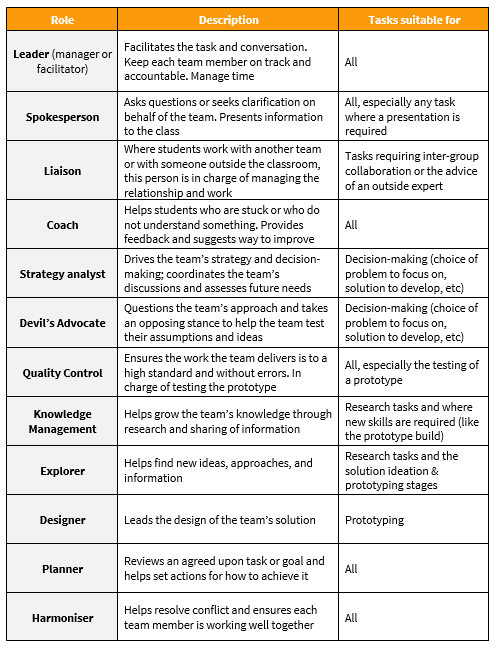

A list of strategic roles is below. Each role has been described and the type of task which might need that role to be played has also been included.

Strategic roles should be chosen on a task by task basis. This is important for a few reasons:

Each task gives students the chance to play a different strategic role, rather than having to fulfil one across the entire project. This allows them to try different roles across a unit to see which ones they like best and which ones their skillset or personality is best suited to. We want students to be generalists, not specialists – allowing them to sample the breadth of strategic roles available helps them build a diverse set of skills

Knowing which strategic roles are available is one thing. We also want students to develop the metacognition of knowing which roles are most important for different types of tasks or different points in the unit. We’ve given students an indication of the sort of task each strategic role might be suitable for to help them, but at the end of the day they can only have four strategic roles per task (one per team member). They are going to have to make choices and trade-offs based on their understanding of the task’s requirements, the team dynamic, and their experience of what has and hasn’t worked in the past. Could they do this task without a team leader and prioritise having a devil’s advocate instead? Or was the last time the group was leaderless in a task such a debacle that this is a must-have role no matter the task?

Of course, this system isn’t foolproof. Students need to actually stick to their strategic and functional roles, which is hard enough in itself. But helping teams take the guesswork out of creating a team driven by synergy goes a long way to stacking the odds in favour of them succeeding.

Do you know an educator who would be interested in learning more about how to build collaborative skills in students? If so, please share this article with them!

If you are passionate about teaching collaboration and want to learn more, get in touch with us at info@edustem.com.au. We’re always happy to exchange ideas with our PBL community!